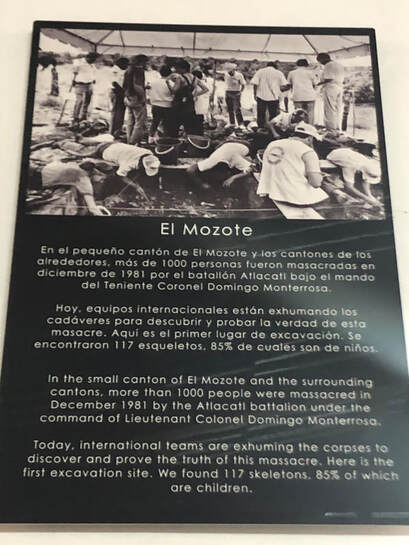

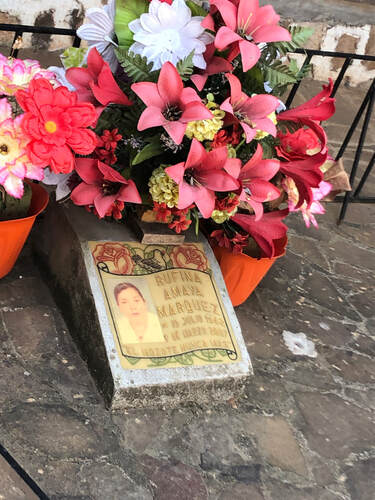

The Memorial Wall at El Mozote. The Memorial Wall at El Mozote. To visit El Mozote is to visit what it is about ourselves that we would prefer to ignore. That we can be cruel and that we can be so indiscriminately. To visit El Mozote is to face that actions are taken, in our names and with our money, that we do not control and that we do not choose. El Mozote places everything in perspective and it is simpler to leave wondering if we ever understand anything at all. In 1981, El Mozote was a remote rural settlement of less than 1000 people. Amid the northern mountains of El Salvador, its inhabitants survived on subsistence farming. When the Atlacatl Battalion, one of what soon came to be known as death squads, arrived in town, it was another day in a series of days when armed men would exert power over the people. It had become ordinary amid a civil war.  Rufina Amaya - sole survivor of the El Mozote massacre. Rufina Amaya - sole survivor of the El Mozote massacre. The facts of December 11, 1981 are this: All of the inhabitants of El Mozote were assassinated, save Rufina Amaya. Girls and women were raped, men were burned to death, children were tortured. Many inhabitants were only identified due to forensic science after the remains were disinterred from mass graves. The perpetrators of the violence were members of the Atlacatl Battalion, which received training at Ft. Benning, Georgia in the United States (at one time known as the School of the Americas). The way that the world learned of El Mozote was in large part due to a woman who, because she did so little, survived the worst of human possibilities. While her fellow women screamed and cried at the soldiers, Rufina prayed and then slipped away. Rufina Amaya told her story for more than a decade and for most of that time it was considered a collection of lies by a peasant woman. If your stomach can stand it, you can read Rufina Amaya’s testimony in the article published by the New Yorker magazine in November 1993 (http://www.markdanner.com/articles/the-truth-of-el-mozote).  I first visited El Mozote in the 1990s. Today it is a town that is nearly unrecognizable from that time. When our van arrived in El Mozote on Thursday, I did not realize that we were across the street from the memorial wall because so many more buildings were surrounding it than when I visited in the 90s. I doubt any American could visit El Mozote and not feel, at best, a twinge of guilt and, at worst, total despair at the depravity of humanity. For the Our Sister Parish partnership, the purpose of bringing American visitors to El Mozote is to help us understand the reality and context that is the living history of El Salvador. The woman who served as our docent at the memorial wall is named Raquel. She is the daughter of a man who was killed in the massacre. She never knew her father. The reason she and her mother survived is because her mother, while pregnant with Raquel, was in the capital city of San Salvador, having been advised that things were getting very dangerous around El Mozote. Raquel is now the same age as my youngest brother. I translated as Raquel shared with us both her family’s history related to El Mozote and the events of the horrendous day. I had to close my eyes to translate one particular sentence. Raquel said that Rufina Amaya’s 8-month-old child, a child the same age as my sister in 1981, was taken from Rufina, thrown in the air by a soldier, and bayonetted mid-air.  Before she died, Rufina Amaya requested that she be buried at El Mozote so she could once again be with her children who were murdered that day. Before she died, Rufina Amaya requested that she be buried at El Mozote so she could once again be with her children who were murdered that day. When we speak of Rufina Amaya as the lone survivor of the El Mozote massacre, we mean she was the lone victim of the atrocity who survived. But there were more survivors of the trauma. Those in the military during conflict are taught to follow orders. The members of the Atlacatl Battalion behaved like monsters, but they were and are human beings. When El Salvador went through the process of the Peace Accords which ended its civil war in 1992, all ex-combatants were exonerated. I had to wonder what the lives of the perpetrators – those who survived the trauma of having done the evil that was the massacre at El Mozote – had been like. Some of them, the members of the Atlacatl Battalion, were killed in later combat. But some survived. Rufina Amaya is said to have told a journalist that for the rest of her life, she could not sleep at night. I doubt she was the only one. I first visited El Salvador when I was 19 years old. It has been a part of my entire adulthood. All of the friends I have here have their own stories of war and trauma and loss, most of which they have never shared with me. The public memorial at El Mozote is miniscule in comparison to the living memorials that are all of the adult population of El Salvador. It must give the parents of today, my peers, who were children during the civil war great comfort that the children of El Salvador today know about the civil war from memorial walls, not from their nightmares.

Annika

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorFeb. 2020 Delegation ArchivesCategories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed